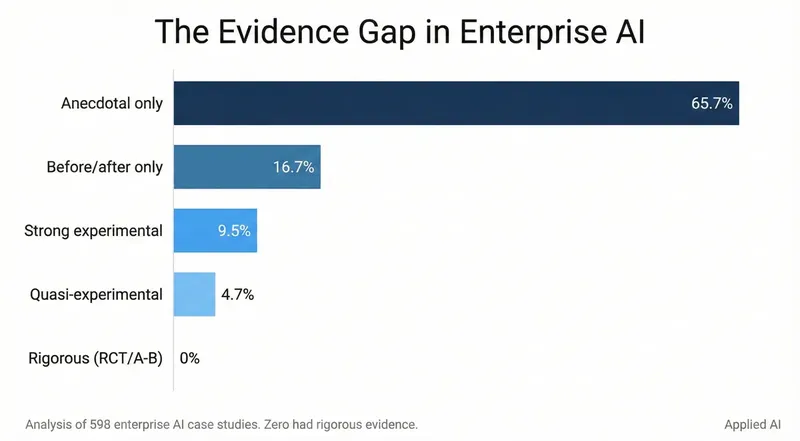

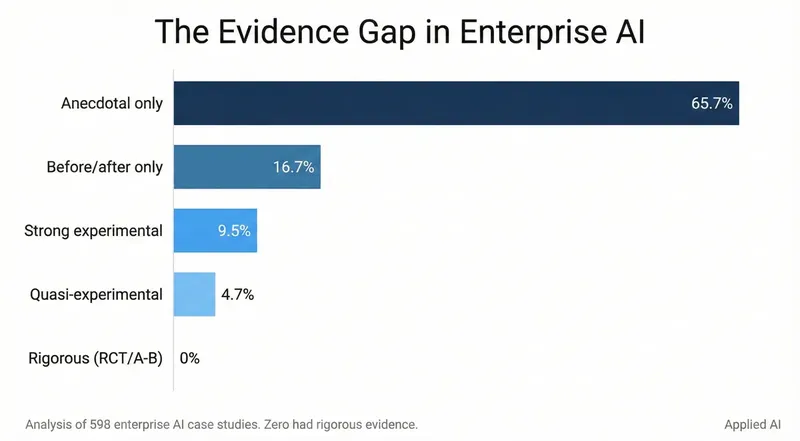

The Evidence Gap

We analyzed 598 AI case studies from ZenML's curated blog aggregation—the largest public collection of enterprise AI implementations (Applied AI, 2025). The results weren't subtle.

Two-thirds of enterprise AI case studies provide no measurable evidence at all. The typical "case study" reads like this: "We implemented an AI solution. It transformed our operations. Our team is excited about the results."

The problem runs deeper than methodology. When we classified the framing:

- 90.5% were explicit marketing showcases

- 84.6% had overwhelmingly positive tone

- Only 1.5% were critical

- Only 31.3% mentioned any failures

This represents survivor bias at scale. Failed projects don't get blog posts. Microsoft's own team described agentic solutions as "brittle, hard to debug, and unpredictable" (ZenML aggregation, 2024). Coda documented that "playground evaluations often passed while production failed" (ZenML aggregation, 2024). These honest voices remain a minority of the conversation.

The Reliability Problem

The structural issue: successful implementations get written up while failures stay quiet, and case studies lack control groups. An implementation that improved metrics by 30% might have improved them by 25% due to the attention effect alone—and we have no way to separate signal from noise.

This creates a practical engineering problem: teams adopting AI based on case studies have no reliable information about what actually works.

Why Evaluation Gets Skipped

Evaluation requires three things that many teams lack:

Clear success criteria. What does "good" look like for your summarization system? Is a summary that's accurate but verbose better than one that's concise but misses nuance? These questions have no universal answers. They require product decisions that many teams defer indefinitely.

Ground truth data. For many LLM applications, creating labeled datasets is expensive and time-consuming. A customer support bot handles thousands of edge cases. A code assistant generates solutions to problems that may have multiple correct answers. Building the "golden set" requires domain expertise and sustained effort.

Organizational patience. Rigorous evaluation takes time. When the competition is shipping features, stopping to measure feels like falling behind. The incentive structure rewards shipping over measuring.

None of these obstacles are insurmountable. But they explain why "vibes-based" evaluation—subjective, unsystematic review based on gut feel rather than metrics—dominates: it's faster, easier, and sufficient for demos.

Synthetic Ground Truth: The Cold-Start Solution

The ground truth problem has a practical solution that's become standard practice: synthetic data generation. Rather than manually labeling thousands of examples, teams use powerful LLMs (GPT-4, Claude) to generate question-answer pairs from their source documents.

The workflow:

- Take your document chunks or knowledge base

- Use an LLM to generate realistic questions users might ask

- Have the LLM generate "ideal" answers based on the source

- Human-review a sample (10-20%) for quality control

- Use the synthetic dataset for automated evaluation

This approach isn't perfect—the synthetic questions may not match real user distribution, and the LLM's "ideal" answers reflect its own biases. But it solves the cold-start problem: you can have a working evaluation pipeline in days rather than months. Iterate on the synthetic data as you collect real user queries.

Frameworks like Ragas provide built-in synthetic test generation. For enterprise deployments, the combination of synthetic baseline + ongoing production sampling creates a practical evaluation foundation.

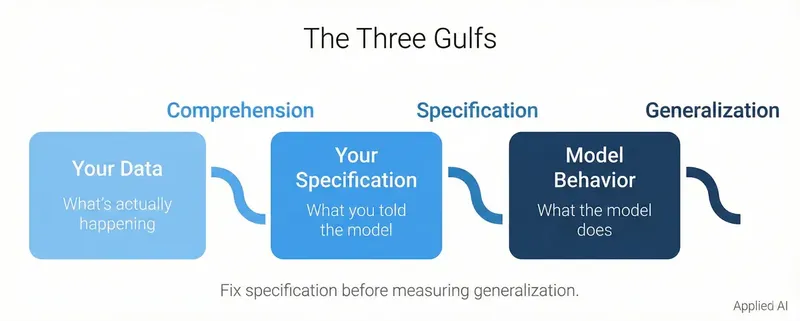

The Three Gulfs

Before measuring, you need to understand why your system might fail. The Maven LLM Evaluation course introduces a useful framework: three "gulfs" that separate developers from reliable systems (Shankar et al., 2025).

The Gulf of Comprehension

The first gulf separates you from understanding your data and your pipeline's behavior on that data. At scale, you can't read every input or inspect every output. You need systematic ways to understand what's coming in and what's going out.

Consider an email processing pipeline that extracts sender names and summarizes requests. You might process thousands of emails daily. Without systematic analysis, you won't notice that the model sometimes extracts public figures mentioned in the email body as the sender—a subtle failure that looks correct at first glance.

The Gulf of Specification

The second gulf separates what you mean from what you actually specify. Natural language prompts are inherently ambiguous. A prompt that says "summarize the key requests" leaves critical questions unanswered: Should the summary be bulleted or prose? Include implicit requests or only explicit ones? How concise?

Underspecified prompts force the model to guess your intent. Different inputs trigger different guesses, creating inconsistent outputs. The fix isn't always better models—it's clearer specifications.

The Gulf of Generalization

Even with clear specifications, LLMs exhibit inconsistent behavior across different inputs. A prompt that works perfectly on your test set may fail on inputs that differ in subtle ways. This isn't a prompting error; it's a generalization failure.

The Key Insight

The Maven course emphasizes a critical principle: fix specification before measuring generalization. If your prompts are ambiguous, you'll waste time measuring variance that isn't actually variance—it's the model making different reasonable interpretations of underspecified instructions.

The practical implication: before building elaborate evaluation pipelines, systematically analyze a sample of your outputs. Many failures are specification problems that can be fixed by clarifying your prompts. Save the expensive measurement for true generalization issues.

The Metrics Landscape

Once you understand your failure modes, you need metrics to quantify them. The choice of metric depends on whether you have ground truth and what you're trying to measure.

Offline vs. Online Evaluation

Before diving into specific metrics, understand where they apply:

Offline Evaluation happens before deployment—in CI/CD pipelines, on golden test sets, during prompt iteration. These metrics gate releases and catch regressions. They're run against curated datasets where you control the inputs.

Online Monitoring happens after deployment—tracking production traffic, detecting drift, measuring user satisfaction. These metrics catch problems that offline evaluation missed because real users behave differently than test sets predict.

Most metrics work in both contexts, but the operational implications differ. Offline evaluation can afford slower, more expensive methods (comprehensive LLM-as-Judge, human review of all failures). Online monitoring needs fast, cheap signals (heuristic checks, sampling strategies, user feedback).

Reference-Based Metrics (When You Have Ground Truth)

N-gram overlap metrics like BLEU, ROUGE, and METEOR measure how much the generated text overlaps with reference text at the word level (Papineni et al., 2002; Lin, 2004). They're fast and cheap to compute.

The problem: they correlate poorly with human judgment. A valid paraphrase that uses different words gets penalized. They're insensitive to factual correctness—a response can have high overlap while being subtly wrong. Use them as coarse signals, not quality measures.

Semantic similarity metrics like BERTScore use contextual embeddings to compare meaning rather than surface forms (Zhang et al., 2020). They handle paraphrases better and correlate more strongly with human judgment of similarity.

The limitation: they measure semantic similarity, not factual accuracy. A sentence that's semantically similar but factually opposite may still score well. Better than n-gram metrics, but still insufficient for high-stakes applications.

Reference-Free Metrics (When You Don't Have Ground Truth)

Most production LLM applications lack comprehensive ground truth. You need approaches that can assess quality without golden references.

Heuristic checks catch obvious failures: response length, format compliance, presence of required elements. They're fast and deterministic but shallow. Use them as filters, not evaluators.

LLM-as-Judge (covered in detail below) uses a powerful LLM to evaluate another model's outputs. Scalable and nuanced, but prone to systematic biases.

Human evaluation remains the gold standard for subjective quality. Expensive and slow, but essential for calibrating automated metrics and handling high-stakes decisions.

Task-Specific Metrics

Different tasks require different approaches:

- Factuality evaluation uses NLI-based methods (does the claim follow from the source?) or QA-based methods (can the answer be verified from the document?). FactCC and QAFactEval are established frameworks (Fabbri et al., 2022).

- Code generation can often be evaluated by execution—does the code run and pass tests? This makes coding benchmarks like SWE-bench particularly rigorous: success means the generated patch actually fixes the bug and passes the test suite (Jimenez et al., 2024).

- Summarization requires assessing multiple dimensions: accuracy, completeness, conciseness, relevance. No single metric captures all of these.

LLM-as-Judge: Power and Pitfalls

The LLM-as-Judge paradigm—using a powerful LLM to evaluate other models' outputs—has become central to modern evaluation (Zheng et al., 2023). It offers unprecedented scale for assessing subjective qualities like helpfulness, coherence, and style.

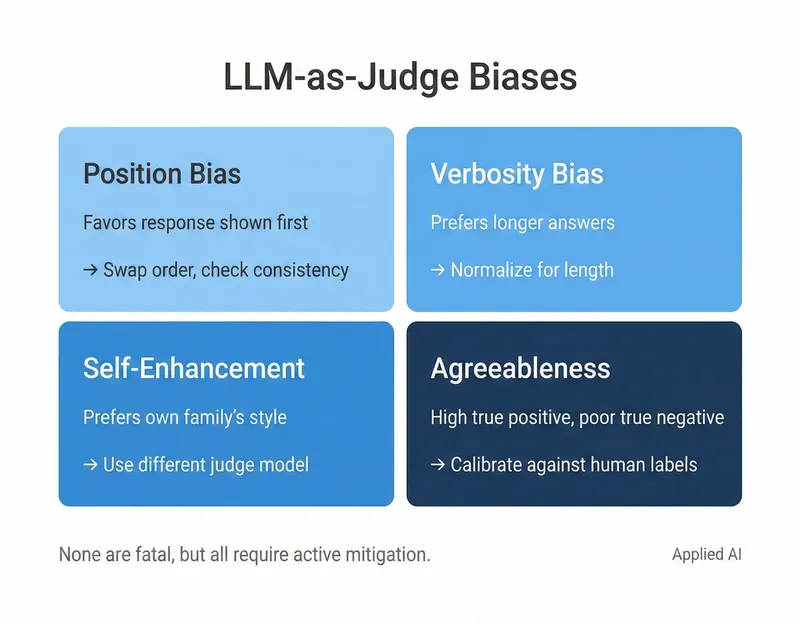

But LLM judges are not impartial. Research has documented several systematic biases:

Position Bias

LLM judges tend to favor the response presented first in pairwise comparisons. In some studies, swapping the order of responses changes the verdict even when content is identical. This isn't a small effect—it can flip outcomes on borderline cases.

Verbosity Bias

Longer, more detailed answers receive higher scores, even when the additional content adds no value. The judge equates length with quality. A concise, correct answer may score lower than a verbose, padded one.

Self-Enhancement Bias

Models tend to score outputs from their own family more favorably. GPT-4 prefers GPT-4's style. Claude prefers Claude's style. This creates circular validation when using a model to evaluate itself.

Agreeableness Bias

LLM judges have high true positive rates (they agree things are correct when they are) but poor true negative rates (they fail to identify incorrect outputs). They're better at validation than detection.

Mitigation Strategies

None of these biases are fatal, but they require active mitigation:

Positional swaps. Run evaluations twice with swapped orders. If the verdict changes, the judgment isn't reliable.

Chain-of-thought prompting. Force the judge to reason before scoring. This reduces some biases and provides interpretable rationale.

Clear, narrow rubrics. Ambiguous scoring criteria amplify judge variance. Specific rubrics with well-defined scales produce more consistent results.

Human calibration. The most critical practice: periodically validate LLM judgments against human-labeled data. This catches drift, reveals systematic errors, and provides the ground truth that automated judges approximate.

Pairwise comparison over absolute scoring. Asking "which is better, A or B?" produces more reliable results than asking "rate this on a 1-5 scale." Relative judgments are easier for both humans and LLMs.

The Cost Trade-off

LLM-as-Judge isn't free. Running GPT-4 or Claude as an evaluator on 10,000 test cases can cost $50-200 depending on prompt complexity and output length. At production scale with continuous monitoring, costs compound.

Sampling strategies help manage this:

- Evaluate 100% of test set changes in CI/CD (offline, bounded cost)

- Sample 5-10% of production traffic for ongoing monitoring (online, controlled cost)

- Run comprehensive evaluation weekly or at release milestones

- Use cheaper models (GPT-4o-mini, Claude Haiku) for high-volume screening, escalate to frontier models for disagreements

The evaluation budget should scale with the cost of errors. A customer-facing chatbot warrants more expensive monitoring than an internal summarization tool.

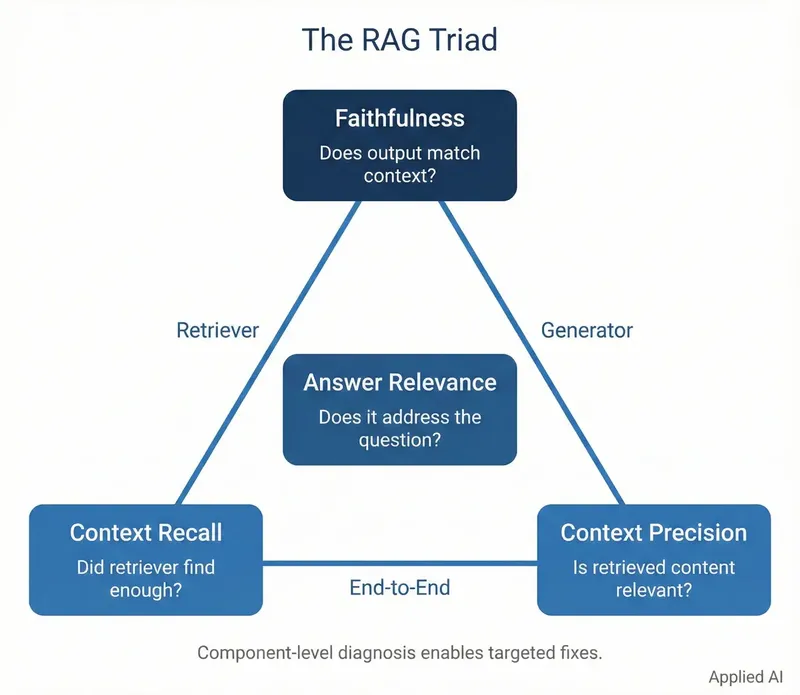

RAG Evaluation

Retrieval-Augmented Generation systems have a unique two-stage architecture that requires specialized evaluation. Failure can occur in the retriever, the generator, or both. The standard approach evaluates them separately using the "RAG Triad" (Ragas, 2024).

Faithfulness (Generator Metric)

Does the generated answer accurately reflect the retrieved context? A faithful response doesn't add information beyond what the context provides—no hallucinations, no embellishments.

This is the most critical metric for enterprise RAG. An unfaithful answer may sound authoritative while being completely fabricated. Evaluation typically works by breaking the answer into claims and verifying each against the context.

Answer Relevance (Generator Metric)

Does the answer actually address the user's question? An answer can be faithful to the context but irrelevant to what was asked. If the user asks about pricing and the system responds with detailed product specifications, it has failed—even if everything it said was accurate.

Context Precision and Recall (Retriever Metrics)

Context Precision measures signal-to-noise in retrieval. Are the most relevant documents ranked highest? LLMs can be distracted by irrelevant information placed early in the context window. High precision means the retriever isn't polluting the context with noise.

Context Recall measures coverage. Did the retriever find all the information needed to answer the question? Low recall means the generator is working with incomplete information—it can't produce a correct answer because the necessary context was never retrieved.

The Diagnostic Value

The RAG Triad's power lies in its diagnostic precision. When an answer is wrong, you can pinpoint the cause:

- Low faithfulness + good context = generator problem (it had the right information but misused it)

- Good faithfulness + low recall = retriever problem (it answered correctly based on what it found, but didn't find enough)

- Low precision = retriever noise problem (too much irrelevant information)

This component-level diagnosis enables targeted fixes. Without it, you're guessing whether to improve your retrieval strategy or your generation prompts.

Implementation Notes

Most RAG evaluation frameworks (Ragas, DeepEval) rely on LLM-as-Judge under the hood, making them susceptible to judge model biases. The choice of judge model significantly impacts scores. Calibrate against human judgments, especially for high-stakes applications.

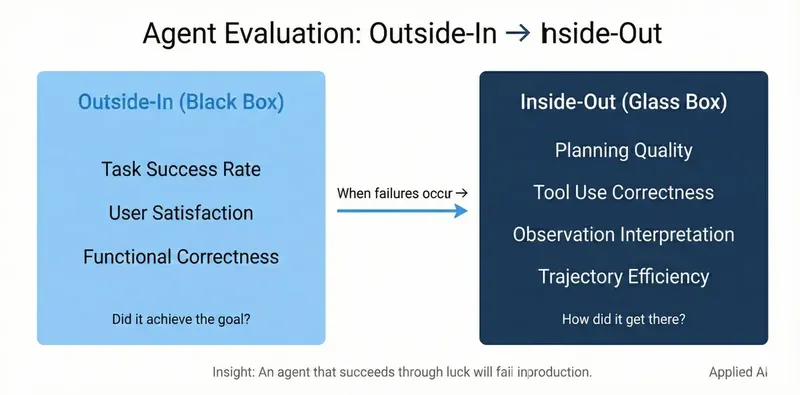

Agent Evaluation

AI agents—systems that plan, use tools, and interact with environments—require evaluation approaches beyond text quality. Task success depends not just on what the agent produces, but on how it gets there.

Google's Agent Quality framework (Subasioglu et al., 2025) introduces a useful hierarchy:

Outside-In Evaluation (The Black Box)

Start with the only metric that ultimately matters: did the agent achieve the user's goal?

Before analyzing internal reasoning, evaluate end-to-end task completion. Metrics include:

- Task success rate: Binary or graded score of whether the outcome was correct

- User satisfaction: Direct feedback for interactive agents (thumbs up/down, CSAT)

- Functional correctness: For quantitative goals, did it actually work?

If the agent scores 100% here, your evaluation may be done. In practice, complex agents rarely do. When they fail, the Outside-In view tells you what went wrong. Now you need to understand why.

Inside-Out Evaluation (The Glass Box)

When failures occur, analyze the agent's trajectory—the sequence of thoughts, actions, and observations that led to the outcome.

Planning quality. Was the agent's plan logical and feasible? Did it decompose the task appropriately?

Tool use correctness. Did the agent select the right tools? Call them with correct parameters? Handle errors appropriately? Research shows tool use is a significant failure mode—cascading errors from wrong tool selection or malformed parameters (ZenML aggregation, 2024).

Observation interpretation. Did the agent correctly understand tool responses? A common failure: the agent proceeds as if a failed API call succeeded, hallucinating onwards from bad data.

Trajectory efficiency. Beyond correctness: was the path efficient? An agent that takes 25 steps and 5 retries to book a simple flight may have "succeeded" but demonstrated poor quality.

The Trajectory Principle

Google's framework emphasizes a key insight: an agent that succeeds through luck will fail in production. If an agent reaches the correct answer through flawed reasoning, that flaw will surface on other inputs.

Task success alone is a sparse signal. Trajectory evaluation provides the diagnostic depth needed to understand and improve agent behavior. But it requires deep visibility into the agent's decision-making—observability that must be built into the system from the start.

Practical Guide: Where to Start

The evaluation landscape is vast. Here's a practical sequence for teams getting started:

Step 1: Define What "Good" Means

Before writing any evaluation code, answer the product questions:

- What dimensions of quality matter for your use case?

- What tradeoffs are acceptable? (Speed vs. quality? Conciseness vs. completeness?)

- What's the minimum acceptable performance?

Without clear success criteria, you'll measure everything and learn nothing.

Step 2: Build a Representative Test Set

Collect examples that reflect your actual input distribution, including:

- Common cases (the 80%)

- Edge cases (the tricky 15%)

- Adversarial cases (the problematic 5%)

A test set of 50-100 well-chosen examples is more valuable than 10,000 random ones. Quality over quantity. Include examples that have historically caused problems.

Step 3: Establish Human Baselines

Before automating anything, have humans evaluate your test set. This provides:

- Ground truth labels for calibrating automated metrics

- Inter-annotator agreement data (how much do humans agree?)

- A reference point for what human-level performance looks like

If humans disagree significantly, your task may be underspecified (Gulf of Specification). Fix that before building elaborate evaluation pipelines.

Step 4: Layer Automated Metrics

Build evaluation in layers:

- Heuristic checks: Fast, deterministic, catch obvious failures

- Embedding similarity: Coarse semantic quality signal

- LLM-as-Judge: Nuanced assessment of subjective dimensions

- Human spot-checks: Periodic validation of automated results

Each layer catches different failure modes. None is sufficient alone.

Step 5: Close the Loop

Evaluation without action is pointless. Build processes to:

- Review failures and add them to your test set

- Track metrics over time to detect drift

- Trigger alerts when quality degrades

- Feed evaluation results back into improvement cycles

The Maven course's Analyze-Measure-Improve lifecycle captures this: evaluate to understand failures, measure to quantify them, improve based on what you learn, then evaluate again.

Conclusion

The enterprise AI industry runs on anecdotes. Our analysis of 598 case studies found zero percent with rigorous evidence. This isn't sustainable. As AI systems handle more critical decisions, the gap between deployed capability and measured reliability becomes increasingly dangerous.

Rigorous evaluation isn't exotic methodology. It's what mature engineering disciplines expect. The pharmaceutical industry has done it for decades. AI has just skipped the step where we prove things work.

The path forward requires three shifts:

From vibes to metrics. Stop asking "does it feel good?" Start asking "how does it perform on our test set compared to our baseline?"

From outputs to processes. For complex systems—especially agents—evaluating the final answer isn't enough. You need visibility into the reasoning that produced it.

From one-time to continuous. Evaluation isn't a gate before launch. It's an ongoing discipline that catches drift, identifies edge cases, and drives improvement.

The industry is flying blind. The tools to see clearly exist. The question is whether organizations will invest in using them—or continue making billion-dollar decisions on anecdotes.

References

- Applied AI. (2025). ZenML Case Study Meta-Analysis. Analysis of 598 articles from ZenML's curated blog aggregation, 2023-2024.

- Fabbri, A., et al. (2022). "QAFactEval: Improved QA-Based Factual Consistency Evaluation for Summarization." NAACL.

- Jimenez, C. E., et al. (2024). "SWE-bench: Can Language Models Resolve Real-World GitHub Issues?" arXiv:2310.06770.

- Lin, C. Y. (2004). "ROUGE: A Package for Automatic Evaluation of Summaries." ACL Workshop on Text Summarization.

- Papineni, K., et al. (2002). "BLEU: A Method for Automatic Evaluation of Machine Translation." ACL.

- Ragas. (2024). "RAG Evaluation Metrics." Documentation. https://docs.ragas.io/

- Shankar, S., et al. (2025). "Steering Semantic Data Processing with DocWrangler." Referenced in Maven LLM Evaluation course.

- Subasioglu, M., Bulmus, T., & Bakkali, W. (2025). "Agent Quality." Google.

- Zhang, T., et al. (2020). "BERTScore: Evaluating Text Generation with BERT." ICLR.

- Zheng, L., et al. (2023). "Judging LLM-as-a-Judge with MT-Bench and Chatbot Arena." arXiv:2306.05685.

- ZenML aggregation. (2024). Various case studies cited in Applied AI meta-analysis.